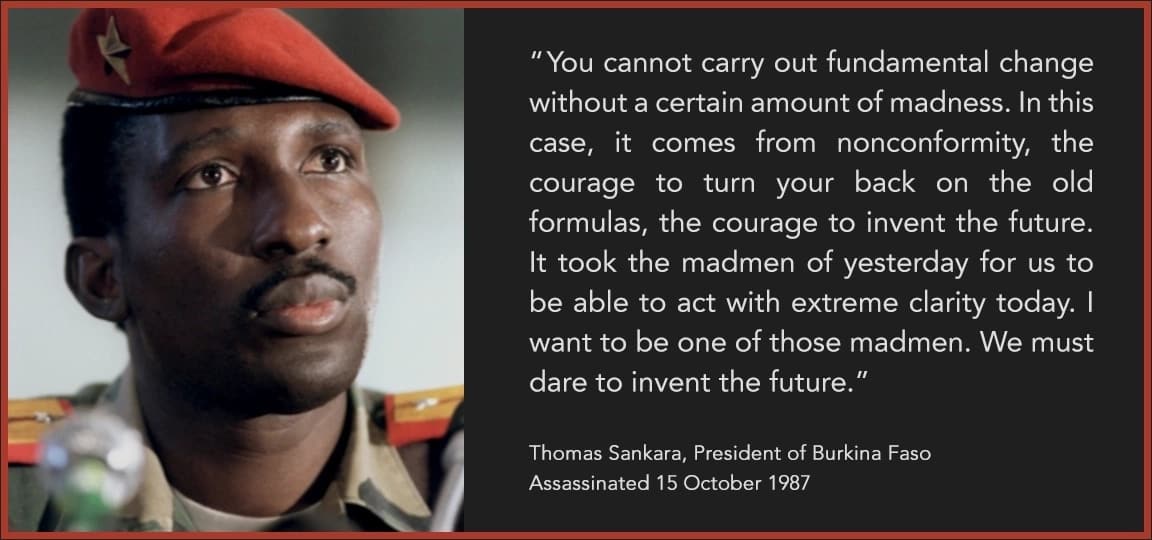

Folklore holds that the former president of Burkina Faso, the late Thomas Isidore Noël Sankara, aka Thomas Sankara (1949-1987), was an accomplished guitarist and because of that, he himself wrote the new national anthem for his country.

The English translation of the Burkina Faso anthem speaks volumes. Anthems of African nation states, such as my own, Uganda, typically gloss over the traumatic colonial period and its sustaining legacy on the continent. Not the Burkina Faso Anthem, which specifically and clearly reminds the world that the colonial period and neo-colonialism must not be forgotten in the context of Africa.

“Against the humiliating bondage of a thousand years, rapacity came from afar to subjugate them for a hundred years. Against the cynical malice in the shape of neo-colonialism and its petty local servants. Many gave in and certain others resisted, but the frustrations, the successes, the sweat, the blood, have fortified our courageous people and fertilized its heroic struggle.”

1st Stanza Burkina Faso National Anthem

Sankara then seemingly used the chorus of the anthem to be a clarion call to remind his people of their humanness and of being part of the human race. Presumably, in order to decolonize their minds of their dehumanisation while under colonisation:

“And one single night has drawn together the history of an entire people, and one single night has launched its triumphal march. Towards the horizon of good fortune. One single night has brought together our people with all the peoples of the World, in the acquisition of liberty and progress. Motherland or death, we shall conquer.“

Chorus Burkina Faso National Anthem

In the second stanza Sankara justified and explained the need for his country’s hard-earned independence from France on 4th August 1960:

Nourished in the lively source of the Revolution, the volunteers for liberty and peace with their nocturnal and beneficial energies of the 4 of August had not only hand arms, but also and above all the flame in their hearts lawfully to free Faso forever from the fetters of those who here and there were polluting the sacred soul of independence and sovereignty.

2nd Stanza Burkina Faso National Anthem

And during his reign, he practiced what he preached. For instance, he:

- Spoke in forums like the Organization of African Unity against continued neo-colonialist penetration of Africa through Western trade and finance.

- Built roads and a railway to tie the nation together, without foreign aid

- Called for a united front of African nations to repudiate their foreign debt. He argued that the poor and exploited did not have an obligation to repay money to the rich and exploiting

In the third stanza Sankara defined and made a call to action to the people of Burkina Faso to revel in their humanity and never to allow another to take it away from them:

“And seated henceforth in rediscovered dignity, love and honour partnered with humanity, the people of Burkina sing a victory hymn to the glory of the work of liberation and emancipation. Down with exploitation of man by man! Forward for the good of every man by all men of today and tomorrow, by every man here and always!”

3rd Stanza Burkina Faso National Anthem

Which explains his egalitarian actions while he was president. Case in point, he:

- Sold off the government fleet of Mercedes cars and made the Renault 5 (the cheapest car sold in Burkina Faso at that time) the official service car of the ministers.

- Reduced the salaries of all public servants, including his own, and forbade the use of government chauffeurs and 1st class airline tickets.

- Converted the army’s provisioning store into a state-owned supermarket open to everyone (the first supermarket in the country).

- Forced civil servants to pay one month’s salary to public projects.

- Refused to use the air conditioning in his office on the grounds that such luxury was not available to anyone but a handful of Burkinabes.

- Lowered his salary to $450 a month and limited his possessions to a car, four bikes, three guitars, a fridge and a broken freezer.

- Redistributed land from the feudal landlords and gave it directly to the peasants. Wheat production rose in three years from 1700 kg per hectare to 3800 kg per hectare, making the country food self-sufficient.

- He opposed foreign aid, saying that “he who feeds you, controls you.”

- A motorcyclist himself, he formed an all-women motorcycle personal guard.

- He required public servants to wear a traditional tunic, woven from Burkinabe cotton and sewn by Burkinabe craftsmen. (The reason being to rely upon local industry and identity rather than foreign industry and identity)

- When asked why he didn’t want his portrait hung in public places, as was the norm for other African leaders, Sankara replied “There are seven million Thomas Sankaras.”

In the fourth stanza Sankara defined his country’s vision:

“Popular revolution our nourishing sap. Undying motherhood of progress in the face of man. Eternal hearth of agreed democracy, where at last national identity has the right of freedom. Where injustice has lost its place forever, and where from the hands of builders of a glorious world everywhere the harvests of patriotic vows ripen and suns of boundless joy shine.”

4th Stanza Burkina Faso National Anthem

And he went about achieving it. For example, he:

- Vaccinated 2.5 million children against meningitis, yellow fever and measles in a matter of weeks.

- Initiated a nation-wide literacy campaign, increasing the literacy rate from 13 percent in 1983 to 73 percent in 1987.

- Planted over 10 million trees to prevent desertification

- Appointed females to high governmental positions, encouraged them to work, recruited them into the military, and granted pregnancy leave during education.

- Outlawed female genital mutilation, forced marriages and polygamy in support of Women’s rights.

Dear reader, you might be wondering what has triggered this search for inspiration from the legacy of ancestor Sankara. Well, I have recently been part of a mind blowing “Intellectual Study Group on Land and Natural Resources” session. The conversations at that session, for me, were myth-busters and paradigm shifters.

I found myself consciously confronted and interacting with terminology and concepts, such as: epistemic certitude or epistemic certainty, epistemic violence, epistemic displacement and frustrate the discourse, among others. This in the context of the disturbing reality of how we, Ugandans, for example, have come to accept narratives that make us invisible and disown us of our land.

Specifically, for example, the obnoxious view that has gained traction during the 30+ reign of President Museveni’s National Resistance Movement, that plenty of our land is idle, not utilised, under utilised, inefficiently utilised, and others derogatory similar. A view that goes unchallenged in the smokescreen of ‘development’ discourse, when it should be challenged for it is a fallacy. Ironically, purveyors of that fallacy unintentionally often contradict it in policy documents when they proclaim and acknowledge the fact that “the back borne of Uganda’s economy is agriculture” by Ugandan smallholder farmers.

What nurtures epistemic uncertainty among us and makes us uncertain of being the owners of our land? What makes us accepting that our land is idle and others of foreign origin know better how to use our land? What is making us accept the rape of our land in the name of ‘development’? These and many more questions such as these need to be asked and answered. Equipped with answers, like ancestor Sankara did, in the short four years he was in power, before he was assassinated, we must retake control of the discourse that defines us; write our own narratives true to our first nations; and live by them.

Source of information about achievements of Sankara @ African and Black History

Leave a reply to Robert oluka Cancel reply